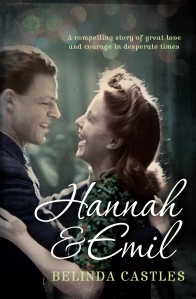

Belinda Castles is the author of Falling Woman and The River Baptists (for which she won the 2006 Australian/Vogel Award). Her latest novel is Hannah and Emil, which traces two characters across Europe, the UK and Australia and charts their complex struggles, and the love that pulls them through. Emil fights for Germany in WWI but is forced from his home with the rise of Nazism in the 1930s. Hannah is independent, talented and resourceful. As a child she longs to be an adult, and as an adult she bravely faces the challenges thrown at her. Hannah and Emil’s childhoods make up the early chapters, they are completely vivid and absorbing and help us, as readers, to understand their decisions later on.

Belinda Castles is the author of Falling Woman and The River Baptists (for which she won the 2006 Australian/Vogel Award). Her latest novel is Hannah and Emil, which traces two characters across Europe, the UK and Australia and charts their complex struggles, and the love that pulls them through. Emil fights for Germany in WWI but is forced from his home with the rise of Nazism in the 1930s. Hannah is independent, talented and resourceful. As a child she longs to be an adult, and as an adult she bravely faces the challenges thrown at her. Hannah and Emil’s childhoods make up the early chapters, they are completely vivid and absorbing and help us, as readers, to understand their decisions later on.

I’ve been lucky enough to meet Belinda a few times as we are/were both members of the Writing and Society Research Centre at the University of Western Sydney. We were also at the same conference in London last year. I thought I’d get in touch with her to ask her a few questions about Hannah and Emil…

I’ve been lucky enough to meet Belinda a few times as we are/were both members of the Writing and Society Research Centre at the University of Western Sydney. We were also at the same conference in London last year. I thought I’d get in touch with her to ask her a few questions about Hannah and Emil…

I know that the story of Hannah and Emil emerged from the story of your grandparents. What did you first find out about them that led to your interest and research, or is it something that’s been in the back of your mind for a long time?

I had always found my grandmother Fay an interesting figure. She was a widow and translator, living in a large flat in West Hampstead surrounded by books, papers and typewriters. She still travelled for work when I was a child. Dad told us that when his father Heinz died, he learned two things about his parents that he had not known before. Fay told him that she was Jewish, meaning that so were her sons: Dad and my uncle. The other thing she told him was that Heinz had had a German wife and son before she met him, and that the son had grown up to fight in the Hitler Youth Army. This pair of secrets, along with the many other intriguing things I had learned about their lives, seemed magnetic. Whenever the subject of the war came up, those secrets were what I thought of.

Their stories do give us a unique perspective (in terms of English language literature) on war, particularly WWII. Emil’s experiences of persecution and discrimination, and the way these experiences distance him from those he loves, makes up much of the narrative. Can you tell us a bit about this struggle? And perhaps about some of the research you must have done on refugees of this era?

I got the impression, perhaps from my father, perhaps from pictures, that Heinz was a loner. His experiences in the First World War, his political opposition to the Nazis, his losses and his ultimate exile from Germany set him apart from others, in my mind at least. It seemed from my reading about the men who came to Australia on the Dunera that the camp at Hay, although unusual in its vibrant intellectual and cultural life, was like other institutions. They may be sociable places, with some of that sociability enforced, but there’s also loneliness, made sharper in this case by the strangeness of the landscape to Europeans and the worry about all those they had left behind. For my character Emil I felt that even when he is among those he loves, and although the people he loves are deeply important to his sense of himself, he is always on some level alone. Perhaps that’s why I gave him a friend on his journey—Solomon Lek. Sometimes the people who go through the same things we do hold a special place, because we don’t have to explain to them what has happened to us. They know because it’s happened to them too, and so there’s no danger of being misunderstood.

Hannah is such a well-drawn character. From her childhood on she is liberal-minded, independent, smart, creative. You’ve talked a bit about finding your grandmother Fay an interesting character. Can you tell us a bit more about developing Hannah’s story? Did you have fun doing it?

It was different to writing the character of Emil. I knew my grandmother for one thing and I remember her as forthright, talented at languages and intellectually engaged. She was fairly crotchety in old age but I was given various documents that stripped away the frustrations of old age and revealed what she might have been like as a girl and young woman. It’s a strange gift to have your memories of someone supplemented in this way. Her unstoppable momentum was in these documents but also her youthful idealism and unwavering loyalty to my grandfather. It was very moving to me to read her memories of childhood, coming back to her fifty years later, as her more recent memories failed her. And in letters to friends in Australia after she had returned to England she remembers when she was ill her friend Valentine climbing in her window with chicken soup and then washing and hanging out the nappies. It felt like discovering treasure to have such moments survive and find their way to me.

One of the reasons I love reading novels is that you feel that you come to understand a person who is not necessarily the most perfect of beings on the outside, because you get past the awkward surface of people. Writing Hannah was that process magnified. I did feel very moved by my grandmother’s life as I learned about it and imagined it into a new form. I felt enriched and expanded by the process.

I’m sure she would be so proud of you, too. The warmth of your discoveries comes through in the character. Finally, there are some stunning images in the novel, particularly of people and bodies: the darkness at the soldiers’ throats comes to mind. These descriptions give the story such resonance. Could you tell us a bit about creating these images? Are observation and note-taking part of this process? Do the images come before or during writing, or even in the rewriting?

Thanks, Angela. Well, during writing I suppose. I am not a big note-taker, although when I’m in the middle of something bits and pieces come to mind and I write them down. But it’s a very enjoyable part of writing to find all these moments waiting for you. That feeling of: I didn’t know I knew that! I think all writers enjoy that. It’s why days with writing in them are better than days without writing in them. Always something new.

—

This post will be added to my tally in the Australian Women Writers Reading + Reviewing Challenge.

Reblogged this on nogoingtolondon.

This sounds like something I should read too. (My parents lived through the Blitz, and lost home and family because of it).

I’ve just reserved it at my local library, thanks, Angela:)

No problem, Lisa. I hope you enjoy it!